(and similar concepts)

doc. Ing. Jaroslav Sivák, CSc., MBA

1. Introduction

This article deals with reflections on the basic concepts common in security practice. We consider “assets,” “risk,” “threat,” “vulnerability,” “resilience,” and others as the basic concepts in security practice.

Why “risky” about risk and similar concepts? There are a large number of various academic works that deal with the definition of these concepts. Terminological dictionaries that have been approved by opposition councils are known, and the legal norms of the Slovak Republic also operate with these concepts. And yet, several binding sources differ. The European Union with its bodies has also contributed significantly to the definition of basic concepts in security management. Several directives use their own definitions of these concepts. These “European” concepts are often then implemented into our norms and into the vocabulary, especially of crisis managers.

“Risky” therefore because the claims contained in this article may not please my esteemed academic colleagues, workers especially from force departments who created and use (or don’t use) terminological dictionaries and create laws and other legal norms in the field of security, and many others.

In an effort to express a certain reality as originally as possible, words such as “attack vector” enter the vocabulary of the security community. Certainly, if we try, we can find an analogy with the mathematical definition of “vector.” But is it necessary…

It is not important whether a given concept is etymologically, grammatically, semantically, and otherwise, the most correct one. It is important that the community that works in security management understands each other and that under a given concept we can imagine as faithfully as possible what the author wanted to express by it and, ultimately, what it describes.

2. Basic Security Truth

The basic security truth, on which most stakeholders agree, is that RISK is the probability (or rate) that a THREAT will exploit a VULNERABILITY of an ASSET and cause an IMPACT on it.

This formulation expresses that we are trying to express a suitable interpretation of a measure that will most faithfully describe what can happen (and will happen) when the variables of this functional1 reach certain values. Risk can be understood as a probability, or another value in the metric that we choose and that will correspond to objective reality and allow us to make judgments about the value – the extent of the impacts that threaten us.

The basic security truth includes both external and internal conditions for the occurrence of a security event. The external condition is THREAT. The internal condition is VULNERABILITY. The subject of the process is an ASSET that is exposed to a THREAT and is VULNERABLE. The result of a THREAT attack that exploited a VULNERABILITY and affects an ASSET is IMPACT. Upon closer examination of security event processes, we would come to other concepts, such as RESILIENCE.

Let’s start from the concept of SECURITY. SECURITY is, quote: “A state of a social, natural, technical, technological system or other system that, in specific internal and external conditions, enables the fulfillment of specified functions and their development in the interest of man and society”2. Critical note: SECURITY cannot be a state! It is a dynamic process whose parameters are of a probabilistic nature. It is therefore a PROCESS. Security is a process that has certain boundaries of minimum and maximum realistically achievable security. This means that there is a non-zero tolerance for disruption of the nominal state. The system must be designed and constructed (arranged) so that it can function even when deviated from this equilibrium state within the range of the above min and max values. These factors can be referred to as RESILIENCE3.

In the following text, we will debate about the part of the basic security truth concerning the concept of RISK.

3. Risk

If we borrow the bon mot about what intelligence is, that it is what is measured by the intelligence quotient, then risk is what is determined by risk analysis.

Risk is, quote: “A measure of threat expressed by the probability of the occurrence of an undesirable phenomenon and its consequences”4. Another definition, quote: “By risk (we understand) the potential for loss or disruption due to a cyber security incident expressed as a combination of the extent of such loss or disruption and the probability of occurrence of a cyber security incident”5. In this sentence, only the “probability of occurrence…” is a measurable variable. The rest is immeasurable. How is it then possible to determine risk in the area of, for example, cyber security?

There are more daring definitions, which probably also give rise to the statement described above:

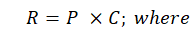

[1]

- R is risk,

- P is the probability that a security incident will occur,

- C is the measure of impact (often only “negative” is meant).

Let’s imagine an example according to relation [1]:

The probability that an airplane will “fall” is 1 fall per 2 to 3 million flights (regardless of distance)6. The probability of an accident per flight is therefore (let’s calculate the variant that 2 million flights):

[2]

If the total damage quantified in money (C) was, for example, 50 million of currency (large aircraft, many victims, loss of Goodwill of the airline…), then according to [1] we should not sit in any airplane.

Correctly, in relation [1] another dimension of considerations is missing, and that is time. The probability that a security incident will occur must be measured in time, i.e., if the probability that there will be a breach of, for example, the perimeter of the digital world (cyber security of the network) is e.g., 0.5, we rightfully ask: “Over what period?” Definitely, relation [1] is not the best. A somewhat better approach would be Bayesian statistics, where risk is defined as the expected value of the loss function. Then there is the area of finance, where Value at Risk (VaR) is often used, which gives the maximum expected loss at a given level of reliability.

In probability theory, we often rely on the so-called probability distribution of the occurrence of a value. In security applications, it is better to use Poisson distributions rather than Gaussian ones, because security processes are burdened with “noise,” i.e., a larger number of factors that also have a probabilistic character are at play.

Let’s use the Poisson approach (we’re looking for the probability of an event over time):

If we assume that an event occurs randomly with an average intensity λ (number of events per unit of time), then the probability that the event will occur exactly k times during a time interval t is given by the Poisson distribution:

[3]

- k is the number of occurrences of the event in time t,

- λ is the average number of events per unit of time,

- t is the length of the time interval.

Using this mathematical model and our example, we would calculate that the probability that no accident will occur is approximately ≈0.99995 and the probability that at least one will occur (complement to one) ≈0.00005.

With such mathematical instruments, we would be able to predict quite accurately with what probability and over what time period a security incident will occur (and how many times it will repeat in a given time interval). The question remains with what probability in a certain time interval this event will occur. First occurrence?

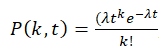

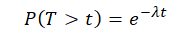

If we are interested in the probability that an event will not occur until time t, we use the exponential distribution, which models the time until the first event:

[4]

If someone wanted to complete our example, then they would calculate that the probability that the event will occur within two years is ≈0.632.

4. Risk in Practice

We have shown that there are relatively precise, but also complex mathematical approaches to determining (calculating) the value of the RISK parameter. However, for common security practice, this approach is awkward, especially for objects with a lower degree of importance. For high-risk objects (e.g., nuclear industry objects), specific (often classified) methodologies are used.

In practice, ready-made software tools for risk assessment, of which there are many, can be used. It is also possible to use your own risk analysis model, then it is necessary to consider especially:

- a) The significance of the organization/system, its attractiveness to the attacker. However, it is necessary to strictly consider the possibility that the organization/system will be used only as the first link in the attack, or as a maneuver to divert attention.

- b) Set the values of impacts that are acceptable for the organization (it can cover them with its resource capacity) and unacceptable. It is appropriate to develop a differentiated structure of impacts.

- c) Determine other parameters (assets, threats, vulnerabilities) according to the security analysis.

- d) Establish a scale for risk assessment (numerical or descriptive). Calculate or determine the risk values on this scale.

- e) The most important step is the interpretation of the risk value from which the level of acceptable risk will result.

- f) Establish risk management for risks that are unacceptable and need to be covered by defensive measures.

Lean more about cybersecurity at Decent Cybersecurity or feel free to contact us at [email protected]

Notes

- A functional is a mathematical concept – it is a function that takes a function as input and returns a number. ↩︎

- Terminological dictionary of crisis management. Security Council of the Slovak Republic. Bratislava 2017. p.8 ↩︎

- Ibid. p.24 ↩︎

- Ibid. p.26 ↩︎

- Act 366/2024 Coll. on cyber security. Collection of laws of the Slovak Republic §3, letter i) ↩︎

- https://asn.flightsafety.org/ ↩︎